The chemical nature of plastic -THERMOPLASTIC

In all of the examples given so far in Introduction, the result of polymerization yields long-chain molecules known as thermoplastics. These materials can flow, becoming essentially plastic, above a specific temperature when molecules can slide past each other due to sufficient energy to overcome intermolecular attractions. Below this temperature, they behave like solids. Thermoplastics are currently the most crucial class of commercially available plastic materials.

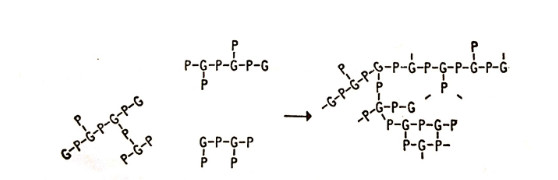

It is however possible to produce other structures. For example if phthalic acid is condensed with glycerol, the glycerol will react at each point, please see below figure 1.1.

This initially results in branched chain structures, as shown in Figure 1.2, where G represents a glycerol residue and P represents a phthalic acid residue. Over time, these branched molecules will connect, forming a cross-linked three-dimensional product.

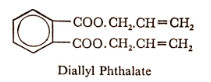

Cross-linking can be achieved in a single step, but in practice, it’s often more convenient to initially create low molecular weight structures known as A-stage resins. These stable, small, branched molecules are shaped and then, with the influence of heat or catalysts, undergo polymerization and some cross-linking, resulting in C-stage resins. These thermosetting plastics include commercial examples like phenolics, aminoplastics, epoxy resins, and various polyesters, despite most being made through condensation polymerization. For instance, diallyl phthalate (Figure 1.3) can polymerize through both double bonds, producing a thermoset polymer.

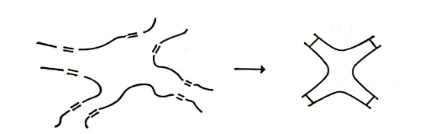

Another method for cross-linking involves initiating with a linear polymer and then linking the molecules by connecting them through a reactive group. For instance, unsaturated polyesters can be cross-linked through addition polymerization across the double bond, illustrated in Figure 1.4

The vulcanisation of natural rubber, a long chain polyisoprene, with sulphur involves a similar type of cross linking.

tobe continue……